As a commercial lifestyle photographer most of my days are spent making images of happy people in lovely settings, living their best life. Once in a great while as an artist, you get an opportunity to make a big difference in a human rights issue, an opportunity to change the way people think about a topic through images. That’s what the “Skin in the Game: Circumcision Cuts Through Us All” campaign to raise awareness of and end medically unnecessary circumcision of babies and children was for me.

I learned about Intact America, a nonprofit committed to ending circumcision, through my wife’s involvement with two books by leaders of the intactivist movement. Marilyn Fayre Milos’s memoir “Please Don’t Cut the Baby!,” co-written by Judy Kirkwood, chronicles the beginnings of activism to spare infants in the United States the trauma and pain of being surgically altered within days of birth. My wife, Echo Montgomery Garrett, co-wrote Georganne Chapin’s memoir “This Penis Business,” about Chapin’s path to activism as a healthcare executive and co-founder of the nonprofit, Intact America.

Finding out that 1.4 million boys born in the U.S. each year have their foreskins cut off, which translates to removal of the protective covering of the head of the penis and the loss of erogenous nerve endings, rang some bells for me. I came to understand that this unnecessary surgery can have a lifelong negative impact on sexual and mental health of boys and men. I felt alarmed at the trauma and pain to which babies and children in this country are subjected—because this was my story, too.

I was born in rural Alabama in 1959 at the tail end of the baby boom. My father, who worked at a papermill, paid the doctor’s delivery fee with $20 and a deer he had killed. People in rural areas or in poverty didn’t have their babies circumcised. Mine was done when I wasn’t yet three years old. I don’t know why it was done at that time, or why it was done at all. It was never discussed. But for years I’d been haunted by shadowy memories of a searing pain in my private parts done in a dark room with my mother present. It was not until I met Georganne Chapin and heard the stories of others that I was able to put together what had happened to me.

But what could I do to help break this cycle of genital mutilation that abuses days old babies and older children?

I thought of how the powerful, heartbreaking images that Gordon Parks made in 1960s Birmingham highlighted the human suffering and brutality during the fight for Civil Rights and made a case from which the viewer could not turn away. The images Eddie Adams made reflecting the inhumanity of the Vietnam War are still on my mind decades after first seeing them. Storytelling with images leads us to engage with issues on a deeper level and makes it impossible for us to walk away from injustice. I decided that’s what I could do for the cause of ending circumcision.

Even though nothing in my portfolio showed the kind of iconic images that could make people change their minds about subjecting babies to circumcision, I shared my vision of activism through story-telling and images with Georganne. We brainstormed and came up with the “Skin in The Game: Circumcision Cuts Through Us All “campaign and in April and June of 2023, I photographed more than 80 participants during two photo shoots in Atlanta, Georgia, and one in Dallas, Texas. Our team made black and white images that connect the viewer to the subjects in an emotional way that draws the viewer into the pain, anger, regret, and sorrow caused by male infant circumcision. Men and women of all races, ethnicities, and all ages are affected, and they all have a powerful story to share.

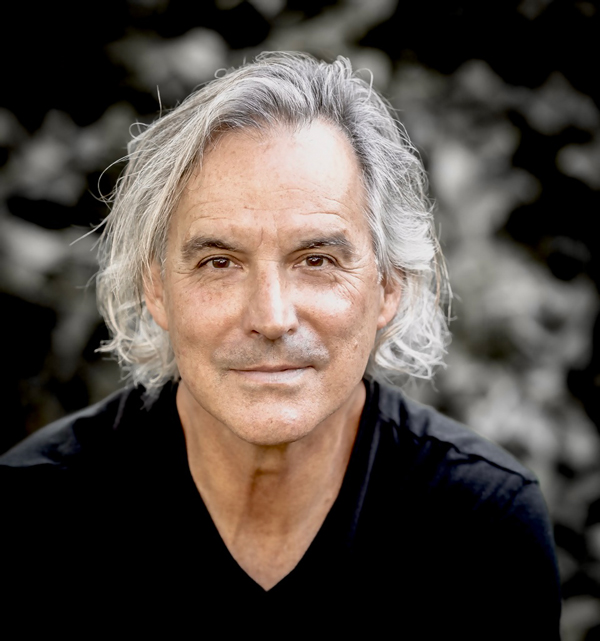

The images are striking in their reduction of visual elements around the subjects. We made the choice to have everyone in denim jeans and simple black tee shirts, to photograph on a stark white background, under classic lighting schemes. This structure highlights the humanity and unifies us as all similar. My goal was to have the viewer’s focus solely on the individual featured in the shot, to his or her face, to their emotion.

We assembled a talented team of creatives to pull these shoots off. Kelly Floyd, community coordinator for Intact America, put out the call for people who would share circumcision stories and allow us to photograph them in this emotional portrait style. Our lighting director, Ken Schneiderman, lit the sets with beautiful and distinctive light. Ray Hardy and Joe Lacerte, as our digital technicians, gave us clean and consistent files. Stephen Mancuso was impeccable with hair and make-up and kind and reassuring to all the subjects who sat in his chair. Kelly Floyd and Echo Garrett interviewed all the subjects. They all made my job easier.

Because I was asking participants to dig into traumatic and deeply personal experiences, I engaged the subjects in quiet, empathetic conversations. My goal was to have them feel safe enough to tap into whatever the subject of circumcision made them feel. This studio and set were a safe place for our subjects to be vulnerable and to share their painful stories.

Everything matters when you are asking people to bare their souls. We even engaged a talented and conscientious caterer, Lisa Callens, for all the shoots so there would be nutritious and comforting food available for all because we wanted to send the message that everyone’s story matters and that we care about their wellbeing. For the Atlanta shoots, we also brought Felicia Guevara, a massage therapist, on site, who gave chair massages. We selected soothing soundtracks for each day but made sure it didn’t interfere with the bonding we witnessed. We wanted to honor people’s willingness to share such intimate stories and do everything in our power to make them feel safe, because truth-telling could make a profound difference for future generations.

What ended up happening surprised everyone on the team. Most people wound up hanging around for quite a while after their shoots and interviews were done. They gathered in pockets around the studio, deep in conversations. Several mentioned their relief at knowing that they were not alone in their experiences.

On the backside of the shoots, my long-time assistant Holly Brown did a meticulous job retouching the final images. Hector Sanchez and Jan Sharrow made inspiring, captivating designs for the campaign. Some of their work is highlighted in the “Skin in the Game” 50-page book that serves as a preview of the art book we hope to produce based on the almost 300 golden images winnowed down from the 30,000 I shot.

The heroes of this campaign are the men and women who shared their stories and gave their hearts on the set. Many found the courage to voice things that they had never shared with anyone. I’ve never worked on a more personally fulfilling professional project or collaborated with such special people—both those who worked on the project and those who volunteered to share their stories with strangers, all of us united in a desire to make a difference.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Kevin Garrett has done work on award-winning campaigns for nonprofits and foundations including The Arthritis Foundation, The Coca-Cola Foundation, Ronald McDonald House Charities, Susan G. Komen Foundation, Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, The Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Trees Atlanta, and Orange Duffel Bag Initiative. KevinGarrett.com https://kevingarrett.com/

This essay and a showcase of the campaign launched in 2024 originally appeared in The Blue Mountain Review September 2024 Issue 32 and is reprinted with permission.